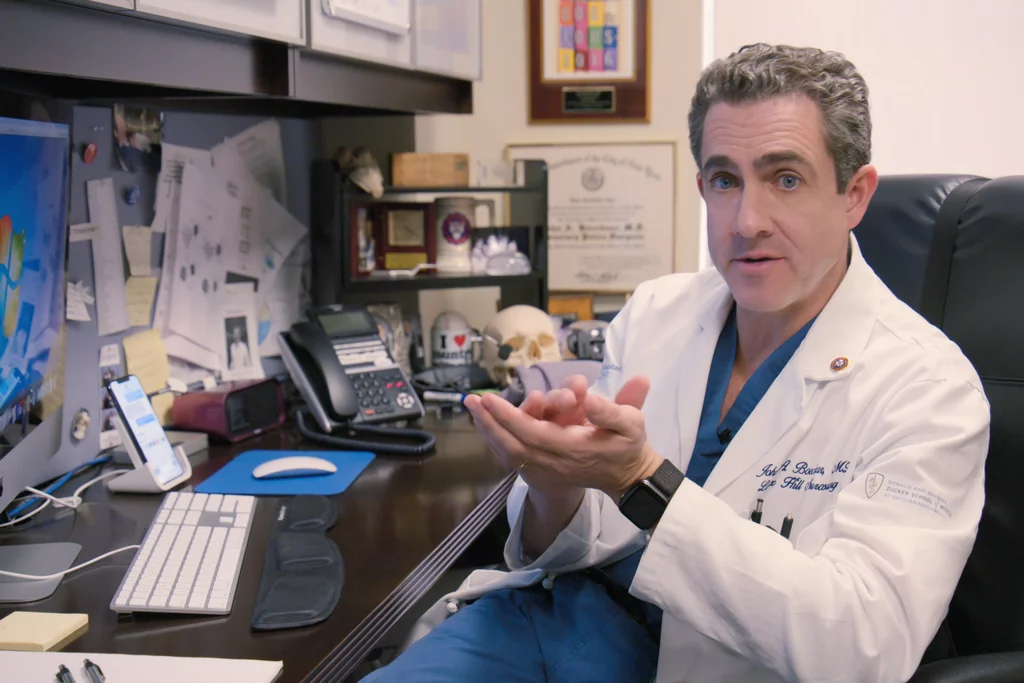

profile: john boockvar, md

Dr. Boockvar as featured on Lenox Hill on Netflix.

Cure Glioblastoma volunteer, Steven Capone, MD, interviewed John Boockvar, MD in December 2020. Dr. Boockvar is Vice-Chairman of Neurosurgery at Lenox Hill Hospital, Professor of Neurosurgery at the Zucker School of Medicine, and is a founding Senior Fellow of Cure Glioblastoma. “Profiles in Neuro-Oncology” is a new regular series of the Cure Glioblastoma Blog.

Dr. Stephen Capone: Dr. Boockvar, what drew you to neurosurgery?

Dr. John Boockvar: You know it’s funny, I just found that I had an interest in the brain. The one thing I say to everybody is, “You like what you’re good at and you’re good at what you like.” When I was an undergraduate at Penn, I had a great professor named Steve Fluharty who started my interest in neuropsychopharmacology. And that’s sort of how I began to get interested in the brain. So, by the time I was a first year medical student, I was tutoring neuroanatomy as a first year. And then I liked it, I was good at it, and I knew I was going to be interested in the neurosciences. My dad is an ophthalmologist, I was interested in neuro-ophthalmology, neurology, and neurosurgery. Ultimately, I knew I wanted to be a surgeon so I put the two together and by the time I was a third year medical student, I really decided to be a neurosurgeon.

SC: That’s fantastic. I think that focuses on the importance of mentorship in something as grueling as neurosurgery.

JB: Well, that’s a hugely important thing. As you train in neurosurgery, you’ll call me back and ask about how you train in neurosurgery, handling the stress, the time commitment, and being compassionate. That’s another whole discussion.

SC: Yeah, each one of those deserves quite a bit of consideration on their own.

JB: Yep

SC: So, how did you make the jump from general neurosurgery to CNS tumors and more of a neuro-oncology focus?

JB: Same thing. I was at Penn doing my residency. It all comes down to who are your models and who are your mentors. I watched a guy named Donald O’Rourke at Penn who was a junior faculty member. I liked how he was balancing his lab work, in the lab once a week and writing grants. In 1998, when I was early in my residency, the world of stem cell biology was born. In Madison, WI embryonic stem cells were first really being isolated. It was on the cover of Nature and Science and so I said, this is such an interesting field. I’m not really interested in embryonic stem cells, although I started getting interested in stem cell biology for trauma, and then all of a sudden I shifted my work. Dr. O’Rourke’s emphasis was on epidermal growth factor receptor signaling in glioblastoma. I saw in the stem cell world that they required EGF for embryonic stem cell growth. So, I put two and two together and started working on GBM stem cell biology. And that’s just how it happened. I started writing grants. I had a good mentor in Donald O’Rourke, I got awards early, I got grant funding early. And my lab work sort of took off from there.

SC: Again, that comes back to mentorship and you had a great team around you. That really let you grow individually and fostered that growth. Hearing that you got grants early on funded is an incredible achievement. I know grant funding itself is its own specialty.

JB: You know, grants beget grants. It’s very hard for a granting agency to grant a grant, particularly nowadays. In the late 1980s, early 1990s, before my time, the NIH had a larger budget and hospitals were making more money, so they were able to give a little more operational money to research. That’s not happening these days. It’s really, really tough. The only advantage you can get is to just get that first grant. It can be a 5k medical student stipend, but it’s a stamp of approval. The other thing I’ll recommend is to keep your CV updated. Don’t be shy. One of the best fortune cookies I ever got is “mediocrity is self-inflicted, genius is self-bestowed.” I still have it on the bulletin board on my wall. The reason why I love it that no one really cares about you or knows what you’ve done better than yourself. I’ve framed every LOR written on my behalf. I keep my CV updated. I’m not shy, without being arrogant. Your job is a bit of spin. That’s just my 2 cents.

SC: It is. I think that’s a very reasonable statement. What do you feel is the most significant discovery in glioblastoma? It can be understanding the molecular basis, advances in immunotherapy, advances in imaging technologies, whatever you’re most interested in.

JB: I think ultimately… if you look at the last 30 years, I’m going to step back from two perspectives. Our imaging modalities have really been the only places we’ve improved significantly over the course of three decades. Meaning that our MRI, much like your iPhone or Samsung, is better at navigation and optics, etc. So are our MRI tools. So, imaging in general has led to a significant improvement in a host of neurological disorders. The preoperative and postoperative imaging of brain tumors in general has gotten quite exquisite, to the point of a 7T magnet. In the late 80s, you were working with a CT scan. Over the course of three decades, that has helped our frameless navigation. We do MRI-guided surgeries that are much safer for patients so my extent of resections can be better. We still have a host of issues. We’re doing some molecular targeting. We have MRI-guided focused ultrasound for a host of disorders. We have MRI-guided lead placement, for example, for Parkinson’s. If I were to look at one thing we’ve done well in, it’s imaging.

Dr. Boockvar performing glioblastoma resection procedure with 5-ALA imaging guidance (courtesy of Dr. Boockvar).

We have made strides in the molecular basis of disease. So that would be the second thing. We’ve gone from very simplistic things, such as 1p/19q co-deletion in oligodendroglioma, to MGMT promoter methylation in glioblastoma, to IDH mutation to now a host of genetic alterations. I would say one of the most important biological bases of understanding of GBM is the heterogeneity of disease, meaning that the genetic markers for one cell may be completely different, even within the same tumor.

I haven’t really answered your question because we’ve really done rather poorly. If you look at what our successful treatments over the course of three decades are, temozolomide which is based on STUPP data from 2005. Bevacizumab, which can be a very potent drug that improves progression free survival but not overall survival, is a good drug. Not quite sure if we’re using it optimally. And the Optune device, which barely works and is based on data without a good control but is FDA approved. That’s 30 years of glioblastoma treatment.

Now, immunotherapy has proven woefully unsuccessful in a host of clinical trials with glioblastoma. And there’s a whole reason for that, basically the immune system does not survey the CNS well. I think there’s a future for improvement. I think artificial intelligence will help some of the molecular diagnostics, for example, of frozen sections. I think AI will hopefully be merged with imaging so the computer will be able to tell what looks like treatment change, or progression vs. pseudo-progression, which is a big issue right now in glioblastoma. Do I think there’s going to be a magic bullet where a single alteration in a gene is going to lead to a treatment of GBM? I don’t. So, it’s a challenging time from that perspective and an exciting time from the technological perspective. As a surgeon, fortunately, it’s actually a great time. I’m using 5-ALA, using a 3-D exoscope, and have great frameless navigation so from a surgical perspective we’re in the heyday.

SC: So, what do you think the future of treatment is going to be?

JB: If we don’t start to understand the blood-brain barrier, who cares? You know?

SC: Yea I think that’s a very forgotten part of this.

JB: Let me tell you how biotech works. Biotechnology starts in non-solid tumors. Hematopoietic disorders like AML, CML. Biotech likes diseases with a lot of people with cancers that are small blue cells because most drugs work in these cancers. It doesn’t have to pass the blood-brain barrier. They’re rapidly dividing. So, when you’re talking about early wins when you’re trialing a drug, you don’t start in glioblastoma. All the drugs that are made, even in oncology, are not looking at the blood-brain barrier. Even 98% of small molecules do not penetrate the blood-brain barrier. So, whether it’s immunotherapy, small molecules, or large monoclonals, unless we have a way to better bypass the blood-brain barrier either using enhanced delivery or direct cell transfer. But again, all these therapies—CAR-T therapy, vaccine therapies, dendritic cells—they don’t get through the blood-brain barrier. So my interest, I just opened a new clinical trial using an omental-cranial transposition where we stick fat from your gut onto the surface of the brain to bypass the blood-brain barrier. That’s where the future lies.We have a lot of good drugs that have been shelved because they don’t bypass the blood-brain barrier. They’re effective in melanoma, in lung. Some of it also is that we’re probably not trialing the right drugs.

I think we’re going to make strides in immunotherapy. Immunotherapy, maybe early on when patients have a better immune system will work, as opposed to in the recurrent setting when patients are on [steroids] and immunosuppressed. I think there is a future for immunotherapy and combinations of immunotherapy agents may work in conjunction with vaccinations.

SC: And as we progress and maybe understand the blood-brain barrier and how to bypass it a little more, things like immunotherapy may be more effective if we can ensure that it’s actually getting to the tumor.

JB: Absolutely. Remember, your testes and your brain are immune-privileged places. You can ramp up your immune system in a lymph node in your axilla. I just got the COVID vaccine so my dendritic cells picked up the coronavirus mRNA and is traveling to release my spike protein into a lymph node and my thymus. But even those T cells that are building my immunity don’t get into the brain. We take out glioblastomas all the time and there are no T cells in there. But, we know that there are a whole host of human diseases like Multiple Sclerosis (MS), or progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy (PML), or encephalitis where there is infiltration of lymphatic cells. The question is when can we get it to work. You know the data shows that patients who get infections in glioblastoma live longer? So we have a trial with a drug out of Australia where we’re giving pieces of bacteria into the veins of patients to try to boost their immune system.

SC: That’s really interesting. To shift a little bit more to the clinical side, when you get a patient that comes to your office, how do you approach planning your treatment for that individual patient?

JB: You know, it comes down to where they are in their disease. I have a clinical trial for every stage of glioblastoma, whether it’s newly diagnosed, first recurrence, second recurrence, or salvage. And the first thing is getting good imaging. You want to make sure the imaging is correct. Where you don’t want to make a mistake is, for example, treating treatment change instead of true tumor progression. And there’s a lot of bad imaging out there. Starting with good imaging is important. Obviously dependent upon the setting, making sure the pathology is good. Making sure the patient is screened for a clinical trial or surgical operation. About 66% of our patients end up in a clinical trial for GBM. The national average is about 5%. We are very proud of that fact. And just to remind you, patients in clinical trials, even if they get the placebo arm, do better than historical controls. The reason for that is that the placebo effect is real and remember there’s something called the Hawthorne effect where observed patients perform better. So, there’s lots of data suggesting that if you’re enrolled in a clinical trial, even if you aren’t randomized to the experimental arm, you’re going to live longer. With the right information and the right talk and the right trials—we want to enlist a lot of our patients in clinical trials.

SC: That’s fantastic. It’s a huge contrast of 2/3 of your patients going to clinical trials versus 5% nationally.

JB: And it makes me crazy. I get patients all the time who reach out to me who have lost the opportunity many times. And it sucks.

Leadership of Lenox Hill Neurosurgery: Drs. Boockvar and Langer (courtesy of Dr. Boockvar).

SC: Yeah, I know a lot of these trials have very specific inclusion or exclusion criteria. If you miss these by a fraction, you aren’t eligible. Having access to these trials early on is fantastic and is a great benefit for your patients. So, what would you say is the most difficult part of your job? I know you spend a lot of time in the operating room and those operations can be grueling, but on the other side you have patients where you have to have very difficult and frank discussions with them at times. What do you think is the most difficult aspect?

JB: Well, I don’t find any of that difficult. To me, that’s the best part of my job. Even the surgery. The hardest part of my job is actually getting funding and finding the time to write grants. The one thing I don’t think is possible anymore is to be a successful and busy complex surgeon and to run a big lab that you are in charge of writing grants for. You need to have a senior post-doc or PhD running the lab. In general, if you’re going to be a surgeon with real surgical excellence, you need to operate a lot. Now I run a lot of human clinical trials, I can do that. But to write a basic science grant and sit there and get a pink sheet from the NIH for an R01, I can’t do it. I write my own clinical trials. I used to write my own grants early in my career, but now my lab is run by two senior researchers and they have to write the grants. And that’s just the way I think the majority of surgeon’s laboratories are run. I sit in lab meetings and go over the basic science, but it ends there. To touch on the subject of how to handle the stress of bad news, there’s a lot of good news when you extend life and give people hope. Every day matters and every year matters.

In our brain tumor center we have a slogan: “We Strive for Five.” We tell every patient we’re going to strive for five years with this disease and we’re going to re-evaluate at that point. We never profess to cure this disease, but we want the survival curve to be increasing. We have data coming out from one of our clinical trials where 31% of our patients live three years, which doesn’t sound like a lot, but is a big number. It’s a big number, I don’t care how you slice it. We want to strive for five and that’s how we approach things.

SC: I think that’s a very reasonable goal and having that honest conversation doesn’t give false hope, but also doesn’t destroy a patient’s hope. It’s a nice balance.

JB: By the way, there’re a bunch of nihilists and miserable people in the field of neuro-oncology. And patients will be really demoralized after speaking to some people in the field.

SC: I was hoping to discuss a little about your research. I know you’re very involved in GBM research, both basic science and clinical trials as you mentioned. Can you touch on what you think is your most promising project right now?

JB: Intra-arterial drug delivery is really my most promising project right now in that if we can better understand the blood-brain barrier, we can selectively overcome it using microcatheter-based technologies. Right now we are selectively disrupting the blood-brain barrier with a drug called mannitol, which is probably not the best way to go about doing this. Hopefully we can better bypass the blood-brain barrier and are trialing a bunch of surgical techniques to do that, using tissue flaps or fat from autologous tissue transfers. To me that’s the most promising and the most necessary. You can do all of this basic science work and develop a great drug, but if it doesn’t get past the blood-brain barrier, who cares?

SC: Exactly. In that regard, how do you balance your clinical and research duties? I know you mentioned that you’ve given up your grant writing duties to the senior researchers in your lab. I know this is something that a lot of neurosurgeons, particularly, struggle with is the balance of clinical duties and research. How do you tackle that?

JB: First of all, surround yourself with great people. And people that can do work and balance your work. So, I delegate a lot of work. I have my research people. When I moved over to Northwell and to Lenox Hill, I brought the entire clinical trial staff from Cornell with me because they’re awesome. I’ll ask them to write papers, to come up with ideas. I had a nurse practitioner write a clinical trial that we have up and running. I get our residents and fellows involved. You get to a point in your career where there is so much you can do. Part of how I mentor is making my junior faculty or my residents write something and I edit it to steer them in the right direction. Fortunately, I’ve been doing this for 15 years and as you go along and get further in your career, when you’re becoming a more complex neurosurgeon, you can spend a little less time doing the grunt work.

Just submitting a paper online, you probably know, can be torture. Just submitting it is torture. But this is what medical students are for. You have to delegate; you have to surround yourself with great people. You have to learn efficiency and balance everything right off the bat.

SC: That’s great. Do you have any advice for patients coping with these diagnoses? When someone comes to talk to you, what kind of advice do you have for them?

JB: First of all, don’t jump on the internet and start Googling stuff because Dr. Google is not a great source of information. It’s a great source of information when you start with the right information. What I like Dr. Google for is connecting patients, for example, to support groups locally or even therapists locally. But don’t start typing “glioblastoma” into Google or Medscape. That is the first thing I say. Google is good if I need help finding, let’s say, a local radiation facility in your insurance plan. That’s where I say use the internet. Then make sure through word of mouth, maybe finding blogs like yours or finding good foundations like Cure Glioblastoma, you start hearing the same names of doctors that patients around you, or likeminded patients, have had good relationships with. And I emphasize relationship over the word “success” or “cure” because the relationship is much more important than a successful treatment half the time. The satisfaction is much better when you have a good doctor who actually cares about you. So, that’s what I tell patients right off the bat.

SC: I think that’s all great advice. It is really a relationship. Obviously, it’s something where everyone’s lives will be changed forever. My last question for you: your show Lenox Hill has been immensely successful on Netflix. I think everyone has watched it at this point. It really opened up medicine, and I think particularly neurosurgery, to the masses. How do you feel that kind of exposure has changed neurosurgery as a field and the public’s view of neurosurgery?

John and Jodi Boockvar in 2020 (L) and 1997 (R) (courtesy of Dr. Boockvar).

JB: I think our goal—you know I didn’t get paid a cent for it—our intent when we agreed to it—and Dr. Langer and I are very like-minded in this way—we thought we were good enough to be filmed. You can’t suck on Netflix. But we also wanted the field to know that neurosurgery was not a bunch of gray-haired, bowtie-wearing people. We’re emotional people. We think we’re very good at what we do. And we love our patients with all of our hearts. And we struggle. We felt we should just tell the God’s honest truth about what it means to be a successful neurosurgeon, and we consider ourselves successful. But we struggle on a day-to-day basis. We still struggle. We have difficulties with our hospital administration, with reimbursement, failures with our surgeries, with complications, strokes, foot drops, weakness, aphasias, and then we have death. And by the way, we also have families. Dr. Langer and I have 8 kids between us. There’s a book called Full Catastrophe Living and for us, we thought the masses needed to know that neurosurgery wasn’t just the bowtie wearing doctor who was away from their family all the time and is a jerk. We’re normal guys with busy family lives and trying to just do the best we can for our patients. The response has been absolutely overwhelming. I could never have pictured this response, and even my wife and kids were skeptical. They all loved the show. We’ve been overwhelmed, and the field of neurosurgery has reached out to us. We really brought out some important ways the department communicates amongst themselves, the reimbursement strategy that isn’t strictly individually based and is group based so we don’t compete against each other, we compete as a team. I don’t steal cases from my spine colleague because I’m not RVU-based. Organizational neurosurgery has come to us asking for change. Educationally, we are changing the way education is done based on our structure. We started our virtual internship, the BrainTERNS, and had 16,000 students this summer from 63 countries. We’re innovative guys and just normal people who wanted the world to see that, and it was successful.

SC: I think the field of neurosurgery in general has opened up their education in general. I think part of it was due to the success of Lenox Hill and part was due to the situation with COVID-19. Now, the educational opportunities in neurosurgery are incredible and expanding every day.

JB: It’s funny and one of the things I’ll take credit for is, after the show, a lot of neurosurgeons, even on social media, became a lot more open. We have such a close-minded field. That was one of the risks, how would people look at Boockvar and Langer? Obviously, we thought there would be a lot of haters and surprisingly there haven’t been. You see more and more people showing their daily lives on Instagram or Twitter and just being themselves, whether it’s Michael Lawton at the Barrow or Ricardo Komotar in Miami. It’s ok to be a normal person.

SC: I think you guys did a great job showing that and I obviously love the show. Very eye opening for a lot of people. Thank you so much for your time and we appreciate everything you do.

Written and transcribed by Steven Capone, MD. Dr. Capone has been a Cure Glioblastoma volunteer since summer 2020 and is interested in a career in neurosurgery.